Butler Beach

Butler Beach

Overcoming Barriers

During the Jim Crow Era (~1900-1964), local and state laws limited the civil rights of African Americans and other non-White Americans.

Racial segregation and voter suppression in Black communities was legally and socially enforced. People who violated (or were rumored to have violated) segregationist policies faced harsh consequences, often in the form of unpunished vigilante violence.

As a result, Black communities throughout America created spaces where they could safely go about their lives. As tourism in Florida grew, several Black-owned beaches and parks were established. Nearby beaches for African Americans included American Beach (Jacksonville), Daytona Beach, and Manhattan Beach (current-day Hanna Park).

Enter Frank B. Butler

A native of southern Georgia, Butler moved to St. Augustine in the early 1910s. He became a well-respected businessman, developing a positive rapport with colleagues and leaders of all races.

Although diplomatic and well-connected, Frank Butler was no pushover. He leveraged his business knowledge and connections to become successful and to uplift the African American community.

His commitment to the Black community guided his business, personal, and political lives. According to the Lincolnville Museum and Cultural Center, Butler came to be known as the "unofficial mayor of Lincolnville."

Butler Beach is Born

In 1927, Frank Butler began purchasing undeveloped land between the Matanzas River and the Atlantic Ocean on Anastasia Island. His vision was to provide St. Augustine's Black residents and tourists with a safe place to enjoy the recreation and resort amenities.

Despite his good standing in St. Augustine, Butler encountered racial discrimination. For example, county officials delayed and denied service requests that he made for Butler's Beach including access roads and water systems. Worries and threats that property values would plummet were common among the area's White residents.

Because of these barriers, Butler became more politically involved to have more influence over such decisions.

The Growth of Butler’s Beach

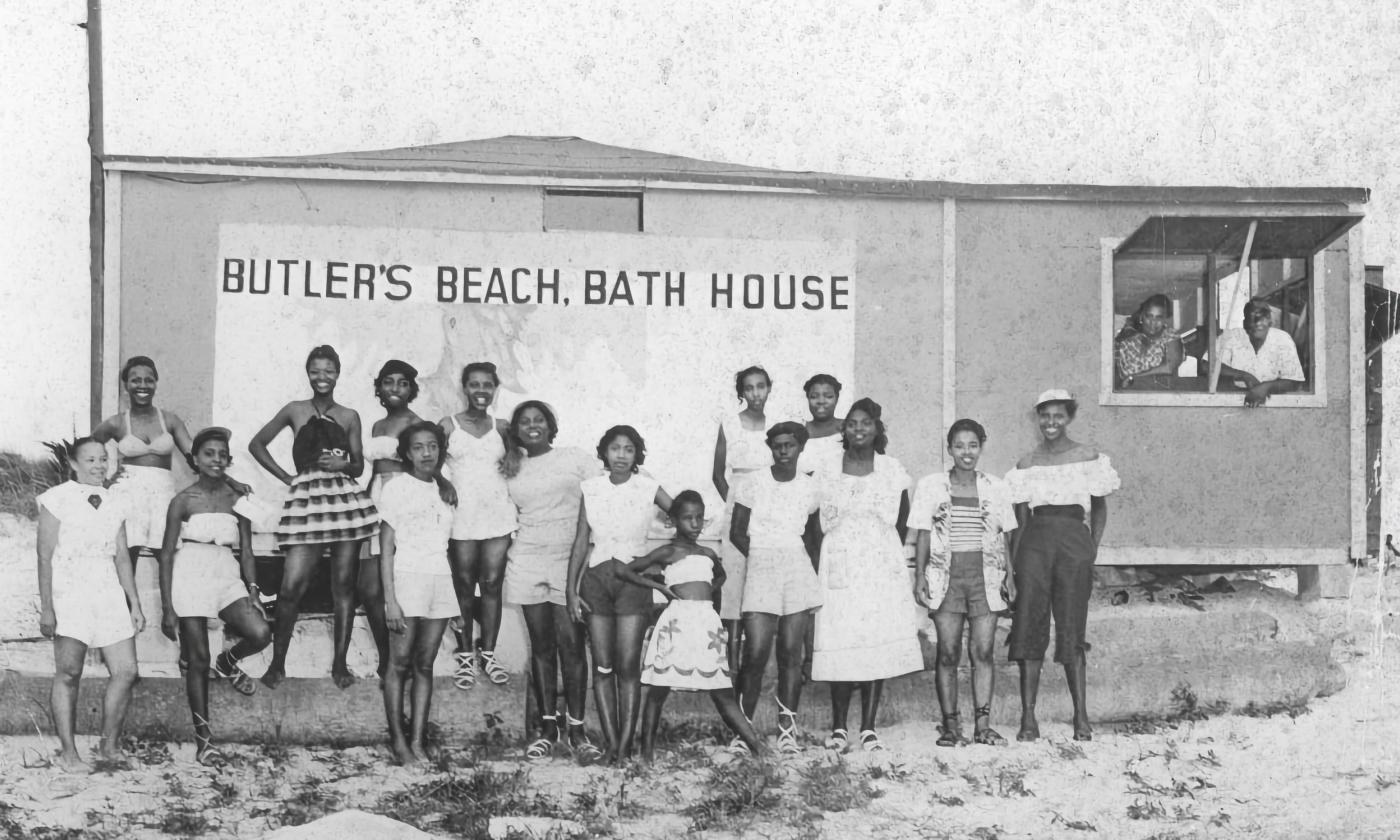

Frank Butler’s vision for a beach resort began to manifest in the 1930s. The property had a beachside and a riverside section, each with its own amenities and businesses. Eventually, a variety of inns, motels, and vacation homes were established.

On the beachside, there was a restaurant, an outdoor pavilion with electricity, a bathhouse that rented out bathing suits and towels — even carnival rides! Lifeguards manned the beaches while security officers kept the resort safe.

The Matanzas River side offered boating, fishing, and cookouts.

By the late 1930s, Butler Beach included Butler’s Sea Breeze Kaseno (1937) and Butler’s Beach Inn (which had a café on the ground floor, fourteen rooms on the second, and eight motel units). By 1947, Butler Beach included a subdivision of residential homes and at least eleven businesses with additional restaurants, cafes, and clubs, many offering music and dancing.

Frank Butler, Generous Benefactor

Although Butler was a focused businessman, he was also caring and generous. He was known to offer to pay for guests' meals and assist families who couldn’t afford a vacation by paying for their lodging.

Fun and Relaxation

Local beachgoers included numerous families, as well as college students from the Florida Normal and Industrial Institute. In 1956, there was a “Glorious 4th of July at Butler’s Beach,” with fireworks, a beauty contest, games, sports, music, and food. Great merriment was enjoyed by many!

State Supports the Growth of Butler's Beach

In September 1956, following the infamous 4th of July Bash at Butler's Beach, then-Florida Senator Pope advocated for a bus route that led to Butler's resort.

Visitation had grown remarkably, and a public bus line ensured that Black residents would not end up at Whites-only Crescent Beach, beyond where they wanted to be. The Senator believed Butler Beach was helping to solve racial issues by providing Black beachgoers with a separate beach destination.

In 1958, Butler sold some of the land to the State of Florida to be developed as a State Park for Black residents.

Butler Beach and the Civil Rights Movement (1951-1968)

The St. Augustine Civil Rights Movement took place throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the most intense years being 1963 and 1964, when Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and his organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) mobilized here.

As the Civil Rights movement picked up steam in St. Augustine, segregated beaches became an opportunity to make a statement. Wade-ins were held at nearby St. Augustine Beach in the summer of 1964. Some of the wade-ins made a national splash, as the St. Augustine Movement was pivotal in the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

Butler’s Beach Inn was one of the many places where Dr. King stayed in 1964 while the SCLC was lending their support to the ongoing efforts in St. Augustine.

College Student Encounters Dr. King at Butler Beach

Jo-Ann Martin Hughes, a Florida Memorial College student from New York, recalls visiting Butler Beach with friends in 1964. They were playing cards in one of the cafes when a few Black men approached them and asked if they were involved in the Civil Rights demonstrations. She said that she was not. Meanwhile, a friend was kicking her under the table. It wasn’t until the men walked away that she was informed that it was Martin Luther King Jr. and some of his staff. Embarrassed she didn’t recognize Dr. King, Hughes became involved in the local Movement.

From Integration to Present Day

Before Butler died in 1973, he worked with the State of Florida to upkeep Butler Beach and some of its amenities. However, after his death, maintenance efforts stopped and the resort fell into disrepair for several years.

Under the Care of St. Johns County

In 1980, the park on the Matanzas River and the Butler Beach area were turned over to St. Johns County with the agreement that they be named in Frank B. Butler’s honor. Today, Frank B. Butler County Park's beachside and riverside are maintained as recreational nature areas.

Legacy

Frank B. Butler was a pillar of the community in St. Augustine for more than 40 years, with his Butler Beach community being the only beach that allowed African Americans in St. Johns County.

Many still recall the great times they had at Butler Beach, as well as the man credited with making them happen.

Thanks to St. Johns County and local historians, Historic Butler Beach and the memory of entrepreneur Frank B. Butler are with us to stay.

Resources

Tap the underlined text to view the following online resources.

Further Reading

Frank B. Butler: Lincolnville businessman and founder of St. Augustine, Florida's historic Black Beach, by Barbara Walch.

- The portrait in the header image of this profile is sourced from the cover of this book.

Great Floridians 2000 program, from the Florida Department of State, 2000.

The Dark Before Dawn: From Civil Wrongs to Civil Light, by Gerald Eubanks, 2012.

St. Augustine, Florida, 1963-1964: Mass Protest and Racial Violence, edited by David Garrow, 1989.

Online Resources

Butler Beach marker text, from the Historical Marker Database.

"Frank Butler Virtual Tour," from the Lincolnville Museum and Cultural Center.

"Butler Beach," blog post from the St. Augustine Historical Society.

"Martin Luther King Jr.'s Anastasia Island Connection and the History of Butler Beach," 2022 article from The St. Augustine Record.

"In 1947, Black residents weren't allowed on beachs in St. Johns County. So, Frank Butler created his own," 2023 article from News4Jax.

"Manhattan Beach, a resort for African Americans, once flourished in Hanna Park dunes," 2018 article from The Florida Times-Union.